Good grief, my first follower. (Welcome, Alpha Signal Five!) I suppose I’d better actually post something now, eh?

I remember my first video game. This is surprising, because my chronological memory is terrible: I don’t remember the first movie I saw in the cinema, or the first time I made a friend, or even my first kiss. I remember that various instances of these happened; I just can’t tell which came first.

But I remember my first video game. It wasn’t even that impressive: I didn’t spend the weeks and months afterwards thinking about it, as I would with many later games, or even seek it out much to play it again. I just remember it, for some reason, a bright silver button of a memory against a backdrop of noise.

I was eight years old, and I didn’t know anything about video games, but I loved pinball. I wasn’t especially good at it, though in the manner of an eight-year-old I thought myself a master; I just thought it was neat, all those flashing lights and little secrets that would show themselves if you could just get the ball to go in the right direction. I would go to the local pub to play their pinball machine, because I grew up in a village that even now consists of just over a thousand people, and so no one cared about eight-year-olds in their pub.

Then one day – I don’t know if it had always been there, and had just never caught my attention before – I turned from the pinball machine and saw that, on the opposite side of the room, there was a strange cabinet. It looked sort of like a fruit machine (what the US calls slot machines), but instead of reels it had a television screen, which clearly displayed some kind of electronic game.

I did have a computer (an Amstrad PCW 8256), but I didn’t really have games for it. It was a two-colour machine, black and green, mostly designed for word processing; you could type in games in BASIC, but I didn’t learn how until much later. And even if I could’ve, the games it would have played were nothing like this. This had full colour, sound, a joystick (or possibly two, I don’t remember), and a word-salad title that was, in fact, so strange to my eight-year-old mind that several years later, after I’d played a bunch of other games and forgotten and re-remembered this one, I found myself wondering if I’d made it up.

After all, what kind of game was called Gals Panic?

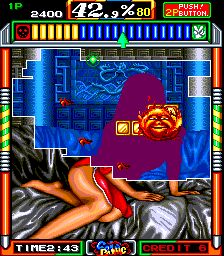

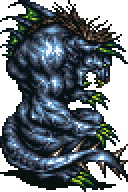

Well, as it turns out, an eroge. Yes, that game I was playing in my innocence had naked, or at least scantily-clad (cursory research suggests the English-language versions were censored), ladies as its reward for victory. This likely would have freaked out tiny!me, but I managed to avoid having my own Itoi moment with the game simply by virtue of being too bad at it to get very far. As far as I remembered, it was just that weird little game with an eerily realistic spider boss – I had some vague impression that maybe the spider was what was making the gals panic – and a strange title.

So Gals Panic, for those who don’t know, is basically Qix with naked ladies. For those who don’t know Qix, it’s a simple game involving a cursor, a playfield and various roaming enemies; the goal being to encircle as much of the playfield with your cursor as you can, thus “claiming” the encircled parts, without getting hit by the enemies. Like many Qix clones, Gals Panic features an extra mechanic to make the basic Qix gameplay more interesting: the playfield hides a picture, and once you claim an area with your cursor, the portion of the picture underneath it is revealed.

Gals Panic, of course, has pictures of women. According to Wikipedia, the first time you clear a stage you simply see the girl in her normal outfit, while raunchier clothes are reserved for subsequent clears. Alternatively, if you do badly enough, the picture underneath changes to something ugly or frightening instead. Since I don’t actually remember many girls in this game at all, I suspect I frequently got the latter.

All in all, it’s a simple game that really has no business being described in as much detail as I have, except for one thing: it was my first video game. And as silly and objectifying as it may seem to my older eyes, my eight-year-old self only saw in it a puzzle, and possibility: the possibility that this thing called “video games” could be much more than just green characters on a black screen.

Like I said, I didn’t really play Gals Panic that much. After the initial thrill of discovery, I moved on to more interesting, fantastical pastures; mostly on a friend’s Amiga 500, which deserves its own post, if not several. From there it was the NES and Game Boy, then the SNES, and from there – well, many things, but there was no eclipsing the SNES, which would be forever after the centre of my gaming world, a trove of seemingly (still) inexhaustible riches. Still, though I never really went back to my inaugural experience, the set of games that I came to know as “the arcade” were always in the background, little slivers of half-understood worlds that peppered my home-gaming knowledge with promises of the future.

Until, of course, they weren’t.

Plenty of people have written about the demise of the arcade. Its impact on me must have been significantly lesser than for those who lived, breathed and slept every Street Fighter version tweak and custom mod; but I still feel the void, occasionally, when I come across a place that in the old days would have had an arcade machine standing there, or nowadays only has one for ironic, nostalgic purposes.

My arcade games, by and large, were more like Gals Panic than Street Fighter: single machines tucked away in the corners of beachside diners, old even for their time but not yet aged enough to be collector’s items. Pac-Man, mostly, or Space Invaders; cigarette-stained cabinets, burnt-in screens. There was something slightly forlorn about them even then, a sense of an era already in its dying throes, these cabinets the last little hold-out of a scene that would soon fade completely. They’d lost their power to excite and enthrall: they were diversions. You didn’t play Space Invaders because you’d had a burning desire to seek out and play Space Invaders. You played Space Invaders because you were there, and it was there, and you were bored – and, if you were me, because it was kind of interesting to note the slight variants and version differences.

I remember clearly one version that, instead of a spaceship, put the player in the role of the little bird from New Zealand Story. It was startling to find, a little surreal: it was probably my first exposure to the idea that a mascot from one series could cross over to another, that that one character from that one game you liked could turn up outside of his appointed role, surprising you. He wasn’t even a particularly huge mascot, not like Mario or Sonic; I was surprised, pleased, to find that anyone else still remembered him, that anybody cared.

I looked forward to going to the one place where I could play that version, even though I didn’t much care for Space Invaders otherwise. It felt more special to play as the bird. It was as if video games – previously, I thought, these isolated stories told by people far away, who handed them down from on high and never would have considered the preferences of a mere player – had reached out and said, “Hey. You. That thing you liked? Have a reference to it, just to make you smile. We notice. We’re listening.” Like the Creation of Adam, but with Taito, and a wide-eyed, ungainly little kid in a backwater English pub, reaching back to a hand redolent of cigarette smoke and stale beer and luminous, digitised dreams.

I played other arcade games, too, more “modern” ones, at actual arcades rather than pubs and beachfront cafes. I was never very good at most of them, but they fascinated me by virtue of always being far bigger, brighter, better than anything the home machines could produce, making me long for the days when we’d have experiences like that in our own homes. Now we do, and to be honest, it’s kind of a let-down. No longer do we need to take special trips to to play a blockbuster game on a souped-up machine, with movie-like visuals and motion controls; we can play them in our homes, and as such they feel a little less special. The arcade is dead, by and large, because home consoles and PCs can do everything it could do and more, just like cinemas are pretty much dead now that DVDs are ubiquitous and having a cinema-grade setup in your own home is no longer out of reach of the middle class.

The arcade was gaming’s attempt at being larger than life. But now that home gaming is pretty much as close to life as you can get, where do we go from here, in order to keep blowing people away?

Flashy graphics and surround sound won’t cut it any more, and the child in me misses that, regrets that we’ve reached an era where lifelike CG is no longer dazzling but simply expected. But on the other hand, if you can no longer keep going up, you start having to branch out in some other direction. The question of what that direction might be, now that we’ve hit the realism ceiling: there’s a thought that dazzles.

After all, as a species, we’ll never stop playing, or inventing new ways to play. That’s my one bright hope for the future of gaming: the fact that, as much as people like to protest that we’ve stopped innovating – as much as I protest it myself, sometimes – we’ll never really stop. And that alone is all we need.

So goodbye, arcades, and farewell. You took us as far as you could in one direction; you did a good job, and you are beloved for it. Now let’s see what the future brings.

Thanks! Looking forward to it!

LikeLike